There are a myriad of different types of bacteria that call our bodies home. Intestinal bacteria that live in the large intestine are grouped together by species. These bacteria populations are known as gut flora (microbiota). The gut flora plays an important role for us by converting undigested food that cannot be processed and absorbed by the human body into nutrients, as well as activating immune cells in the intestines to protect the body from pathogens.

This article provides basic knowledge about the colon, gut flora, and the intestinal environment.

Basic Knowledge About the Small and Large Intestines

To learn more about gut flora, let us first look at the functions of the small and large intestines.

Role of the Small Intestine

The main function of the small intestine is to absorb nutrients and water.

The food we eat is first digested in the stomach, where it is turned into mush, and then mixed with digestive enzymes in the small intestine, around 6 to 7 meters long, for approximately 3 to 5 hours. It is further broken down and absorbed with water from the epithelial cells in the intestinal tract. The absorbed nutrients are then carried throughout the body in the bloodstream.

Role of the Large Intestine

The main roles of the large intestine are to absorb water unable to be absorbed in the small intestine and to metabolize undigested food.

Undigested food is metabolized by the intestinal bacteria that reside in the large intestine, and the residue is excreted out of the body in the form of feces. The large intestine is shorter than the small intestine, approximately 1.5 meters in length. Undigested food remains in the large intestine for approximately 10 to 40 hours, depending on what it contains.

Check The Condition of Your Colon! 3 Ways to Improve Colon Health in Just 2 Weeks

The functionality of Japanese people’s colons is continuing to deteriorate. It was once said that Japanese people had stomach cancer while Western people had colon cancer. This was thought to be due to differences in diet, but due to the westernization of food in Japan, Japanese people are facing the same problem…

What are gut flora?

Why do gut flora exist in the human body, facilitating the functionality of the large intestine and regulating the intestinal environment?

Intestinal Bacteria Are Microorganisms

“Intestinal bacteria” does not define a single type of bacteria, but rather it is a general term for the microorganisms that live within the intestine.

Did you know that the history of microorganisms is much longer than that of us humans? The earth was born 4.6 billion years ago, and proteins and nucleic acids, the source of life, appeared about 4 billion years ago. 400 million years later, about 3.6 billion years ago, microorganisms were born. Humans were born “only” about 3 million years ago. Microorganisms have existed on the earth far longer than humans.

Over a long period of time, microorganisms have come to exist everywhere on earth, including in the oceans, in the soil, and in the bodies of animals. We cannot help but respect the vitality and fertility of the myriad microorganisms that exist.

Introducing the latest findings on gut flora, which can also be used a personal data

The intestinal environment has been the focus of much attention in recent years with the craze over gut health; the latest findings on intestinal flora are now known to be deeply correlated with health and illness.

Gut Flora as Personal Data

In our large intestines…

Types and Numbers of Intestinal Bacteria

In outwardly expelled stools, there are approximately 100 billion intestinal bacteria per gram. The total number of intestinal bacteria present in the entire intestinal tract of an adult person can weigh up to 1-1.5 kilograms, and the total number of bacteria in the intestinal tract is over 40 trillion. The number of cells that make up the human body is approximately 37 trillion, so there are far more intestinal bacteria living in the intestines than that.

There are roughly 1,000 types of intestinal bacteria existing in the intestinal tract, and each person houses different types of intestinal bacteria. It is said that there are about 160 types of intestinal bacteria common to most people, including BB-12 Bifidobacterium.

Recent studies have shown that the type of gut flora differ depending on the region and race in which one lives, and that the flora of Westerners, who consume a high-fat, high-protein diet, tend to be dominated by Bacteroides spp. while those in countries with a diet rich in carbohydrates and vegetables tend to have more Prevotella spp. intestinal bacteria.

Furthermore, the composition of gut flora is not constant throughout life. For example, after a Japanese person immigrates to the U.S. and has lived there for two to three years, the balance of gut flora may be similar to that of the intestines of Americans due to dietary habits, etc. Dietary habits have a stronger influence on the balance of gut flora than race or region.

Intestinal Bacteria From Mother to Child

When do intestinal bacteria take up residence in the body?

Because the mother’s womb is sterile, there are no intestinal bacteria in the baby before birth. The baby’s first encounter with intestinal bacteria is during delivery. As the baby is birthed from the uterus through the birth canal, it comes into contact with bacteria in the vagina and anus of the mother, and these bacteria first enter the baby’s body.

Contact with bacteria, such as resident bacteria flora on the skin when the father, mother, or midwife picks up the baby, also affects the formation of the baby’s gut flora. As the baby grows, the intestinal flora is formed through contact with many bacteria from the outside world. By age 3, a child’s composition of gut flora is almost identical to that of an adult and is said to be determined to a certain extent.

The State of the Intestinal Environment as Determined by Stool

Intestinal bacteria are invisible to the naked eye, but there are ways to examine them by analyzing stools. With the evolution of testing methods, it is becoming possible to examine the types and composition of intestinal bacteria to determine any risk, such as if there are any bacteria that may cause disease.

However, constant testing is burdensome, so here is a rough guide to assessing your intestinal environment.

If your stools are too hard or soft, there may be an imbalance in the gut flora. The color of healthy stool is yellowish-brown to brown. If the stools have a strong odor, it may be due to excessive eating of meat products, leading to heavy decomposition.

A Guide to Checking Stools

It proves useful to check the stool for consistency, color, and odor.

- Watery: Stool in a liquid state (no solid body)

- Muddy: Irregularly shaped, muddy stools

- Slightly soft: Wrinkled, half-solid stools

- Normal: Smooth, soft, sausage-like stools

- Slightly hard: Cracked, sausage-like stools

- Hard: Sausage-like hard stools

- Pellet-like: Small, hard stools that are reminiscent of rabbit feces.

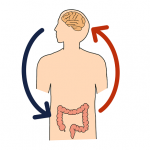

What is brain-gut correlation?

The intestines and the brain are connected by nerves that stretch throughout the body called vagus nerves. The two organs are closely related as they exchange information with each other. The relationship between the interconnected brain and intestines is called the “brain-gut correlation.”

Recent reports have documented the disruption of gut flora due to neurological disorders such as depression, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting the gut’s strong influence on the brain. A unique hypothesis has also been proposed that gut flora determine food preferences.

For example, suppose that a person who normally does not eat many vegetables suddenly craves them only when traveling abroad. This may be caused by intestinal bacteria that prefer the nutrients in vegetables, which send signals to the brain.

Much is still unclear about the brain-gut correlation. As research continues to advance, more is likely to be revealed.

This article was supervised by the person listed below.

Teruaki Matsui, Teikyo Heisei University

Professor, Department of Health and Nutrition, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Teikyo Heisei University

Graduated from Nihon University School of Medicine. In 2000, he became a lecturer at Nihon University School of Medicine, and in 2012, he became an associate professor at Teikyo Heisei University.

He was appointed as an expert member of the Pharmaceutical Affairs and Food Sanitation Council of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in 2001, an expert member of the Food Safety Commission, Cabinet Office in 2003, a councilor of the Japanese Society of Gastroenterology in 1998, a councilor of the Japanese Society for Experimental Ulcerology, a director of the Japanese Society of Geriatric Gastroenterology in 2000, and a director of the Japanese Society of Digestion and Absorption in 2015. His research specializes in general gastroenterology and clinical application of functional foods.